A Revolution in our Time

TL;DR A history of the Black Panthers for young readers

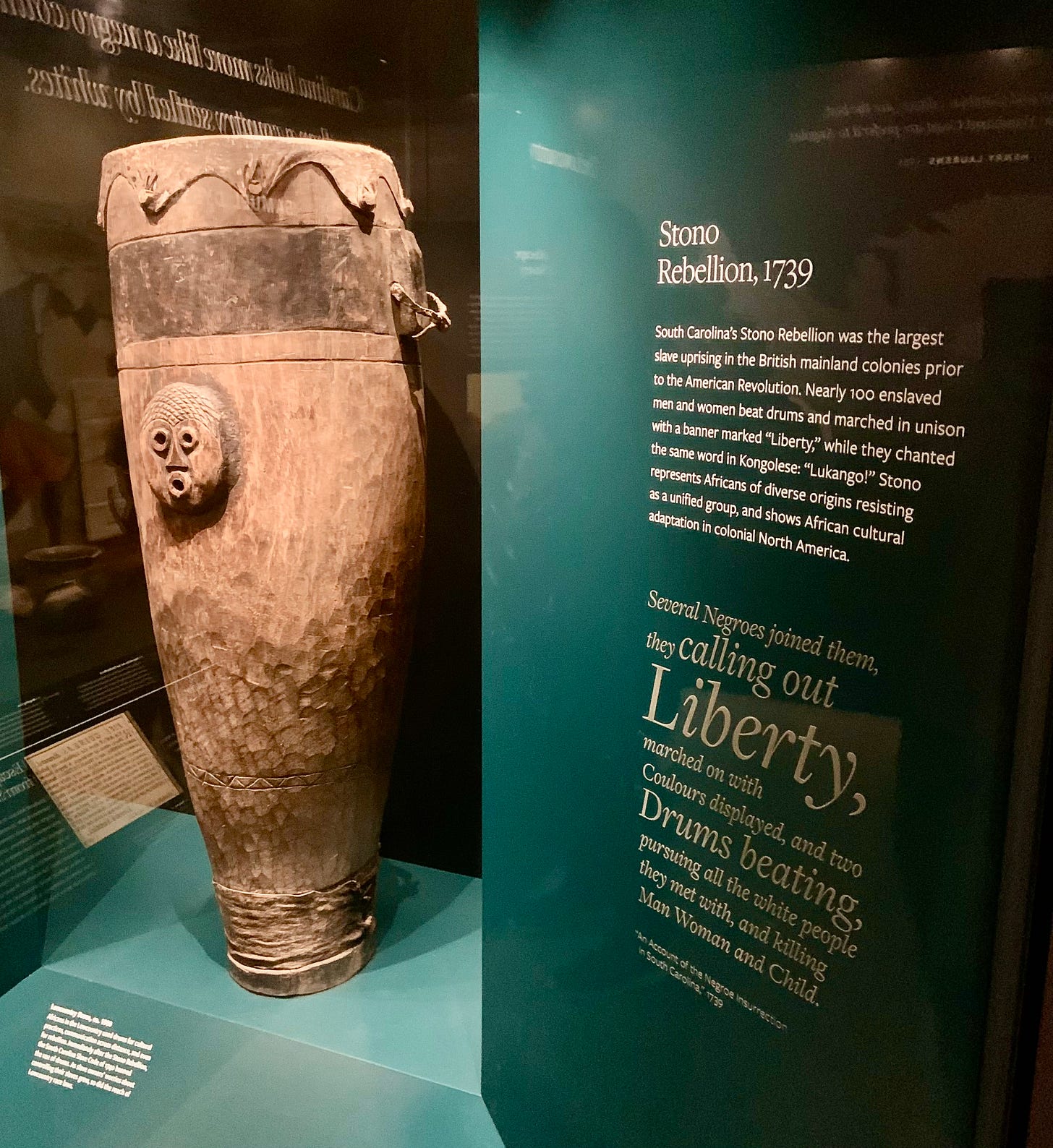

Recently, I visited the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, for the second time. Lead designer David Adjaye and lead architect Philip Freelon, based in my town of Durham until his death from ALS in 2019, created a stunning building clad in bronze-colored metal lattice. The design is meant to evoke the melding of the traditions and art of Africa and the diaspora.

What most people come to see, though, are the history floors below ground. The path leads from the start of the transatlantic slave trade through several centuries of slavery, then the Civil War, Reconstruction, decades of savage segregation, and the fight led by Americans of African descent for their freedom.

The light is quite low on these floors, I imagine to keep visitors’ eyes on the objects and texts. This is a photo I took of a middle school group starting the section on the Middle Passage, with the diagram of the Brookes, an infamous slave ship, in the background. The diagram was used by abolitionists to show people how barbaric and cruel the trade was.

Since this was my second visit, I was looking for things I’d missed the first time around, soon after the museum opened to huge crowds. One of those things was how the museum represented a part of our history that’s often overshadowed by the story of the civil rights movement. That’s the Black Power movement that followed, in particular the story of the Black Panthers.

The museum makes it clear that enslaved people always and at great risk opposed their captivity and fought for freedom, either through legal means, escape, or violent rebellion. It also seemed to me that the curators—subtly and through the strategic use of space—kept my eye firmly focused on the more familiar story of the civil rights movement and non-violence and away from the less discussed and much more controversial legacy of the Panthers.

Some images went by very quickly. Here, for instance, is a facsimile of the Greensboro, NC, lunch counter, site of a famous 1960 non-violent sit-in (with delighted kids packing the interactive displays) below a quickly moving video that, briefly, shows Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), and H. Rap Brown (Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin). The photo flies by without context or even names.

I don’t fault the curators. They are catering to a general public, among them many school children, who likely don’t know the basics of this history, suppressed as it has been for far too long. But this does bring me to the point of this newsletter, which is to praise to the heavens a book for kids that digs deeply into this part of our poorly understood past.

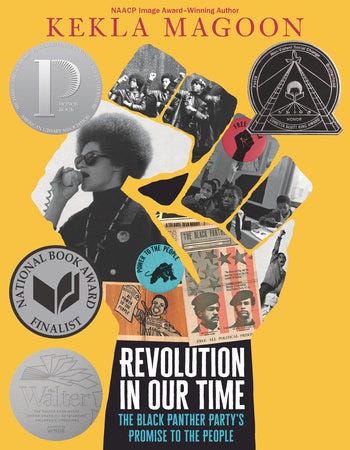

As Kekla Magoon writes in her spectacular Revolution in Our Time: The Black Panther Party’s Promise to the People, people speak of the Panthers “in hushed tones, as if history itself could overhear.” Her book is a necessary and long overdue deep dive into the roots of the Black Power movement, its connections to the fight for civil rights, the emergence of the Panthers, and their destruction at the hands of law enforcement.

For me, it was a thrilling read, with so much I thought I knew (and didn’t) and mostly what I should have known and neglected to find out.

Not for nothing was Revolution in Our Time a National Book Award Finalist, a Coretta Scott King Author Award Honor Book, a Michael L. Printz Honor Book, and a Walter Dean Myers Honor Book. Especially at a time when books like this are being vilified and banned, this is essential reading not only for kids but for adults who want to know more about this history.

What follows is my interview with Magoon about the book and about her amazing breadth as a writer of books for kids.

How did you come to embark on this project?

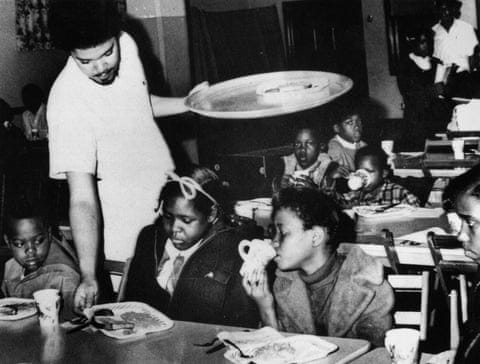

I grew up studying the civil rights movement, and yet never encountered much information about the Black Panther Party. I had one association with the name: Black men with guns, and the idea of that seemed scary to me. So I was very surprised when I stumbled upon an article about the Black Panther Party’s free breakfast for schoolchildren program because it didn’t gel with my impression of the group. The Black Panthers had fed breakfast to children? Yes, they sure did—thousands of children every day, in over forty cities around the country.

Learning this blew my mind and made me wonder what else I didn’t know about the Panthers, which turned out to be a LOT. Far from simply a group of “Black men with guns,” they were an extremely dynamic, truly revolutionary organization which had set out to support Black communities, to educate and empower young people to be active citizens, and ultimately to transform our society in deep and powerful ways. I felt angry that this history had been kept from me as a young person, and I wanted to be sure that it wasn’t kept from the next generation, so I started researching and writing Revolution in Our Time.

You start the book with this invocation: “For all of us, that tomorrow may be better than yesterday.” How do you think the legacy of the Black Panther Party contributes to this goal?

The Panthers were very forward-looking. They made a point to empower young people, in hopes of creating an engaged and educated population who would be positioned to effect positive change across all of society. We continue to strive for a better tomorrow, and the Black Panther Party’s legacy pushes us in that direction in several ways. Former Panthers continue to do important organizing work and young people coming up today can learn as much from their ongoing example as from studying the organization’s history.

You begin the history of the Black Panther Party in 1619. Explain the reasoning behind this choice and how it helped shape the book.

I felt that to understand the full weight of the forces that made young Black people in the late 1960s feel like “picking up the gun” was the best and only option, readers needed to understand the hundreds of years of history that preceded that moment. The book comprises three sections: first is the pre-civil rights movement history of the US, then comes the history of the civil rights movement and Black Power movement, with specific focus on the Panthers, and finally we conclude with a glimpse of the post-Panther decades, bringing us up to present day. Connecting to the present was equally as important as conveying the full past. This history is not meant to solely live captured in a book, but to inform young readers as they make decisions about how to act in the world today.

I imagine most students study the civil rights movement but don’t go into depth on the Black Power movement and the formation of the Panthers. As you note in the Preface, people speak of the Panthers “in hushed tones, as if history itself could overhear.” Explain why you think one story gets more attention than the other?

The Panthers’ truth gets overlooked largely because of who typically tells our history. We study history through the lens of whiteness (in addition to maleness, straightness, and cis-genderedness) in the mainstream US education system. History that views these past four hundred years through a different lens is typically othered, and even sought to be erased.

Black communities teach about the Panthers, but they do it in homes, churches, community centers, and parks.

It is lessons learned through access to people who lived the history. I grew up in a predominantly white community, and so these lessons were scarce. The Panthers were a powerful organization, but much of their power came from their willingness to challenge the white power structure and the economic status quo that continues to imbue white people with greater resources. It has always been in the interest of whiteness to tell the story of the civil rights movement as one of equality and “non-violent” protest, one with a happy ending for all, which of course, is not quite true of the world we actually live in.

One of the key differences between the Civil Rights movement and the Black Power movement that helped create the Black Panther Party is the relationship with the issue of violence. The Panthers advocated self-defense but that was never an option for most civil rights activists. How have readers responded to this difference?

Civil rights activists consciously committed to non-violent passive resistance. They made a concerted decision not to fight back in the face of violence—police violence, white supremacist violence, etc.—even if it killed them. So, the civil rights movement’s relationship with violence was essentially, “we will take the violence that comes to us, to prove that such violence is wrong.” A lot of people were injured and died as a result of that approach. It also helped demonstrate the cruelty of white supremacy and put visual imagery to the concept of racism. The Panthers, on the other hand, advocated self-defense, saying “we will NOT take the violence that comes to us. Instead we will make it known that we will fight back.” Consequently, they succeeded in preventing a lot of violence that might otherwise have happened at the hands of police and white supremacists. When this difference is clarified, and readers begin to see that it’s not a question of “civil rights activist = nonviolence, Panthers = violence,” then they start to understand this moment in history on a deeper level.

You did an immense amount of research for this book, which includes great visuals. What story or personality surprised you the most? What piece of the Black Panther Party history was hardest to research or write about?

The hardest part about researching the Panthers is that much of what was written about them in mainstream publications in their era was either false or exaggerated or skewed. These are sources that would normally be considered primary sources, and still have to be considered primary on some level, but also cannot totally be trusted to tell the full truth. Some of the stories that surprised me the most were about the lengths the police and FBI went to as they tried to disrupt the Panthers’ work. They infiltrated the organization, tried to lead members astray, incited violence, and repeatedly destroyed food and resources that were meant to help struggling people. It’s disheartening, at best, to see concrete evidence that the government was more interested in keeping Black people from gaining any political power in the country than it was in actually helping them survive or thrive.

How has writing this book shaped the way you think about how young people are brought to action in favor of making the world a better place?

The civil rights movement and the Black Power movement alike were fueled by very young people—college students, high school students, middle school students, even children were the primary engine of the protests that took place throughout the 1950s-1970s.

When we teach the history, we tend to focus on the adults, the Dr. King or Rosa Parks-type people who seem grown and settled and mature, but that’s not who changes the world. That’s not who really shakes things up. It’s always the teenagers. Researching and writing this book reminded me of that, and hopefully reading it reminds (or teaches) young people this truth and inspires them to deploy their own power.

At a time when books about Black history are being banned, what has been the reaction to your book? What has been the best reaction you’ve had to the book?

The best reaction is simply young people reading it and finding resonance with it. Anytime I hear of a young reader who’s been carrying it around in their backpack for weeks (it’s a big, heavy book!) or sleeping with it under their pillow because it meant something to them, I know that the effort that went into the book was worth it. I’m fortunate that the book hasn’t been specifically challenged in very many places, but I suspect it’s because the places where it was being bought for schools and libraries in the first place are not the epicenter of book banning. I choose not to worry too much about it (in terms of my specific book—I worry a lot about the state of our country as I reflect on these issues!) and try to trust that my book will somehow find the readership that needs it most.

You write fiction, non-fiction, and short stories as well as books for middle-grade and young adult readers. Is there one theme or intent that unites your work?

Most of my books touch on themes of identity, community, empowerment, and social justice, regardless of the genre or style or topic that I’m working on.

What’s next for you?

I have quite a few books in the pipeline, with three coming out in Spring 2024. Blue Stars, Mission #1: The Vice-Principal Problem comes out March 5 from Candlewick Press. It’s a middle grade graphic novel series I co-wrote with Cynthia Leitich Smith, illustrated by Molly Murakami. We’ll be having our launch party at a bookstore in Minneapolis!

On April 30, my YA novel Prom Babies comes out from Henry Holt. It’s an intergenerational story with alternating perspectives, about three girls who got pregnant on prom night eighteen years ago, and their three kids getting ready to go to their own prom in the present day.

Finally, The Secret Library comes out from Candlewick on May 7. This is a middle grade time-travel fantasy about a girl who discovers a library of secrets—each book-like volume transports her to a different moment in time, where she learns secrets of friends and family alike, and she must learn to navigate secret-traveling as she figures out her own destiny.