This year marks the 21st anniversary of the opening of the US Naval prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, for detainees captured after the terrorist attacks on New York City, the Pentagon, and US commercial aircraft on September 11, 2001.

Almost 800 men have passed through Guantánamo. Currently, the prison holds 30. Of those, 16 pose no threat and have been cleared for release (three of them have been waiting to be freed for over 13 years).

One of the 9/11 plotters held there is Ramzi bin al-Shibh, recently declared "unfit for trial" due to the prolonged torture US officials subjected him to. According to a Defense Department Medical Agency report, al-Shibh is now "psychotic" and suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Guantánamo has been called the most expensive prison on earth—and perhaps in history. According to the New York Times, the per-prisoner cost shakes out at roughly $13 million. The total cost since the prison began receiving detainees after 9/11 is rocketing toward a billion dollars.

In the New York Times, Capt. Brian L. Mizer, a Navy lawyer who has represented detainees, called it “America’s tiniest boutique prison, reserved exclusively for alleged geriatric jihadists.”

Surely, all this served a purpose? No. US military tribunals have convicted only five detainees (that’s roughly $20,000,000 per conviction). Most of those held were entirely innocent: the wrong person or sold for bounty to US authorities and entirely innocent. Others were mere foot soldiers with nothing to do with 9/11. The handful that did participate in the attacks have been tortured so brutally that they are permanently disabled.

Guantánamo is a fun-house mirror of injustice, an utterly failed boondoggle, a human rights disaster that Washington has yet to address. So how to continue to inform the American people about what they’ve bought with their tax dollars? How to get beyond apathy and a willed forgetfulness about how badly we as a nation stumbled after 9/11?

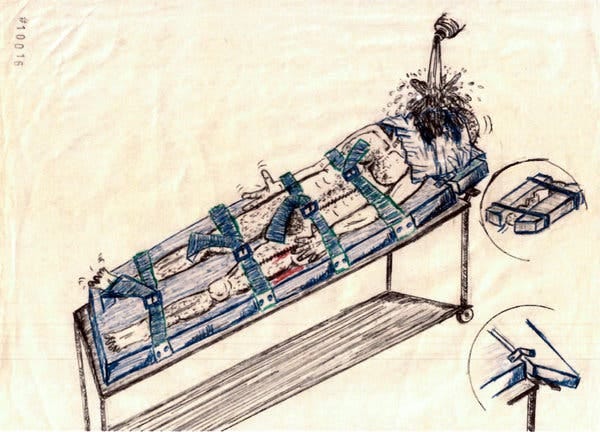

A book that takes a surprising and effective approach is Guantánamo Voices: True Accounts from the World's Most Infamous Prison. Journalist Sarah Mirk and a team of graphic novel artists tell the stories of 10 people who worked or were imprisoned at Guantánamo. The beautiful illustrations somehow convey the horror of the place in a vivid and unique way.

Guantánamo Voices is especially good for teenagers learning about this period in history. Each artist brings a different approach and sensibility to the stories Mirk collected. Here’s my interview with Sarah (and subscribe to her newsletter here).

Tell me how you came to edit this volume of graphic novel chapters about Guantánamo Bay and the people who work there and were imprisoned there.

I started thinking about this book 10 years before I got the chance to make it. In 2008, I was living in Portland and was photocopying a small zine at a collective art studio space. The person next to me was also making a zine, so I asked them about it. They said, “It’s about my time working as a guard at Guantánamo Bay.”

This shook me and I had to know more.

That zine-maker turned out to be Chris Arendt, an art student from Michigan who had been deployed to Guantánamo after they joined the National Guard. They felt very conflicted about their job at the prison and joined the veteran organizing group Iraq Veterans Against the War.

A nonprofit run by a group of former Guantánamo prisoners, CAGE, invited Chris to come on a speaking tour with them around England. I asked to go along on the trip and ran a blog documenting the experience, which I called Guantánamo Voices. This was in January 2009, the month Obama was inaugurated, so there was a lot of hope that the U.S. would soon close the prison. Instead, it remains open today. Traveling around with Chris and the former prisoners, who included author Moazzam Begg, changed my life profoundly. I got to see how these people who had been forced into opposite sides of a deeply dehumanizing environment could find common humanity together, and try to work toward a future that included healing and accountability.

I knew I wanted to make a book about these stories, but I didn’t have any of the skills I needed. When I was keeping that blog of the trip, I was 22. I didn’t know anyone who had written a book. I had never made a nonfiction comic. So over the next ten years, I worked as a journalist, wrote several other books, and started reporting comics—all with this Guantánamo project burning in the back of my head. Finally, in 2018, I had the skills and resources I needed to put together a book proposal and pitch it to publishers. Once Abrams ComicArts said yes, I spent the next two years researching, writing, interviewing, and editing the book.

You approached this by conducting interviews and compiling information about ten people with very different relationships to the prison. How did that idea come about? What were some of the challenges in using these interviews?

I want the book to feel like it addresses the question of why Guantanamo exists and what impact it has had. I wanted the book to be grounded in the powerful experience I had of seeing people on opposite sides of the barbed wire finding a common humanity together. There are many other books written about Guantanamo, many of which are very powerful and informative. The gap that I saw was a book that included numerous peoples’ stories and weaving them together to create a deep understanding of how the prison was built, why it continues to exist, and what life is like for the people trapped there.

Doing this work was very challenging. My brain was immersed in the details of torture, imprisonment, and Kafka-esque legal nonsense for the two years I worked on the book. And I felt an immense burden to honor the people who trusted me with their stories. I want the book to do right by them—and doing right means having an emotional impact on readers. The goal of the book is to hit readers in the heart, and thereby change the cultural narrative Americans have about Guantánamo—the one built on lies that the government has repeatedly told.

You also worked with different illustrators with very different styles. Why was that important? What does the graphic approach bring to this very difficult and horrific subject?

This is a unique approach to an anthology. Most comics anthologies have multiple writers—so each chapter is a different writer and artist. I did all the research and interviews for this book, then asked different artists to illustrate each chapter. This helped the book maintain a consistent tone and narrative structure throughout, while each chapter feels distinct. I wanted each chapter to have a different visual voice, since each chapter is about a different person’s story. The visual tone is meant to match the tone of each story.

I used a chapter of the book, based on Moazzam Begg’s experience as a detainee, for a human rights class. There’s something about the graphic format that really connects with young people. Why do you think that is?

I’m so glad you used that chapter in your class, it’s very important to read the stories of the prisoners themselves. Since people who have been imprisoned at Guantanamo are not allowed to travel to the United States, it can be difficult for their voices to reach people here.

I think that comics connect with everyone, not just young people. Comics have a unique ability to capture an emotional reality. Artists often say that comics are a perfect medium for expressing things that feel impossible to say in words. Art Spiegelman describes this as comics being a medium for the unspeakable. Often, words fall short in trying to capture our emotional worlds—especially in trying to articulate feelings that result from senseless violence. In a comic, a reader can see someone’s face and body and know how they feel, without needing words to tell them. Comics artists can use many tools—color, line-weight, moments of silence—to express feelings that feel impossible to express in words. In this way, I think comics build empathy. In a well-done comic, the reader is feeling what they see on the page.

Ten years ago, I polled undergraduates and discovered that most supported the death penalty (without knowing much about it). Now, support has declined sharply because of more awareness of the realities of mass incarceration, structural racism, and actual innocence cases. Today, though, most undergrads will say they support torture (also without knowing much about it), believing that torture is the only way to acquire information to prevent future terrorist attacks. How do you see Guantánamo Voices in the effort to not only educate young Americans about the history of torture but also to demonstrate how deeply harmful it can be to individuals (detainees, their families and lawyers, as well as many guards and military personnel)?

I have been very upset to see how Americans do not seem to care about the torture we’ve committed or remember the people we’ve incarcerated in the name of our own freedom and safety. But I don’t blame people—especially people who were born after 9/11—for not knowing what we’ve done at Guantánamo. Since day one, the U.S. government has created a convincing myth about the prison—that it’s a “safe, humane, and legal” prison where imprisonment without end is necessary to ensure Americans’ safety. Through four different presidencies now, the government has invested an astonishing amount of time, money, and resources into building and maintaining that myth. It’s hard to counter that narrative when it’s the first one people learn about the prison.

I see this book as doing what I can with the skills and resources I have to try and push back against that narrative and ask people to see the reality of what we’ve done and continue to do. Obviously, it’s not enough, but it’s what I have to offer.

Guantánamo is built on white supremacy, xenophobia, and Islamophobia. I know that this current generation of college students cares a lot about creating a more truly equal world, one that is built on white supremacy. I hope that the book illustrates how this prison was built by people and can be un-built by people. While the stories in the book are grim, the through-line that I hope readers take away is that these absurd and harmful structures were not inevitable—they were intentionally constructed by the white men with a lot of power in the government. And like any structure, they can be changed.

How has writing this book shaped the way you think about how young people are brought to action in favor of engaging with the past, injustice, and human rights?

Writing the book made me reflect a lot on how I learned about unjust situations when I was a kid. I distinctly remember in fourth grade learning about the incarceration of Japanese Americans in internment camps during WWII. When I was learning that history, in the early 90s, the internment was presented as a horrible mistake—a government decision based on racism that irreparably harmed the lives of millions of people. As a kid, I thought I would surely be “on the right side of history” and speak out if anything like that ever happened again.

It wasn’t until writing this book that I learned that California only started teaching that history to kids right at the time I entered elementary school. It took 50 years for the government to formally apologize for what it had done. For many, many years, the mainstream narrative about the internment of Japanese Americans was that it had been necessary. It took decades of people speaking out against that narrative, writing their own stories, interviewing their families, and advocating for change because the mainstream story started to shift. And it took many more years of activism before that understanding made its way into our education system.

Writing this book was very hard because there is not a happy ending. Guantanamo is still open. There are still over 30 people imprisoned there indefinitely. There has been no accountability for people who approved and committed torture. There has been no justice, repair, or healing for the people we hurt. I hold onto hope that by shifting Americans’ understanding of the prison, we can see accountability and true justice—even if it takes decades.

Guantánamo Voices is not only visually rich. You also pack a lot of information between the covers. What has been the best reaction you’ve had to the book?

One of the hardest things about trying to convey the reality of Guantánamo is that journalists are not allowed to talk to people who are currently incarcerated there. So there’s no way to interview the people imprisoned there today. But when we got a rough draft of the book done, I gave it to one of the lawyers who is featured in the book and she sent it to her client at Guantánamo. He read the book and sent back a handwritten note saying he liked it. That note made me cry. It felt so astounding to be able to reach across the chasm the U.S. government has created between the prisoners and the rest of the world.

Will the book be translated into other languages?

That’s not up to me, a publisher needs to buy the foreign language rights. I would love to have it translated all over the world. So far, it has been translated into Arabic.

What’s next for you?

I’m working on a guide to creating nonfiction comics, with my friend and Nib colleague Eleri Harris. The book is currently called “Drawn from the Margins” and will be the first-ever book about the craft of making comics journalism. It’s due out in 2025 from Abrams ComicArts. In the meantime, this year I’m the Applied Cartooning Fellow at the Center for Cartoon Studies in Vermont. That means I get to spend all my days immersed in making comics!

BANNED BOOKS WEEK

Banned Books Week is from October 1-7, 2023 (see my newsletter here). It’s been wonderful to see so many writers and groups writing and talking about the importance of the right to freedom of expression.

But my favorite spokesperson will always be LeVar Burton (who I think of as Kunta Kinte from the original miniseries “Roots” and Geordi La Forge from “Star Trek: The Next Generation”). My children think of him as the host of “Reading Rainbow.”

As the honorary chair of Banned Books Week, Burton is a tireless promoter of books for all readers. “This is as important as it gets,” he notes in this interview.

I couldn’t say this better than Geordi!

Thanks for reading — please leave a comment and share!