These days, the news is a constant assault. That’s deliberate. The current administration in Washington wants us overwhelmed, off-kilter, exhausted. They want people to throw up their hands and say, “To heck with all of this” (this is a swear-free newsletter, though I am pretty sweary these days).

Paying attention, as hard as it is, is itself an act of protest and resistance. So is insisting on clarity and truth in all of this mess. How do we do that?

In part, by standing up for words and what they really mean.

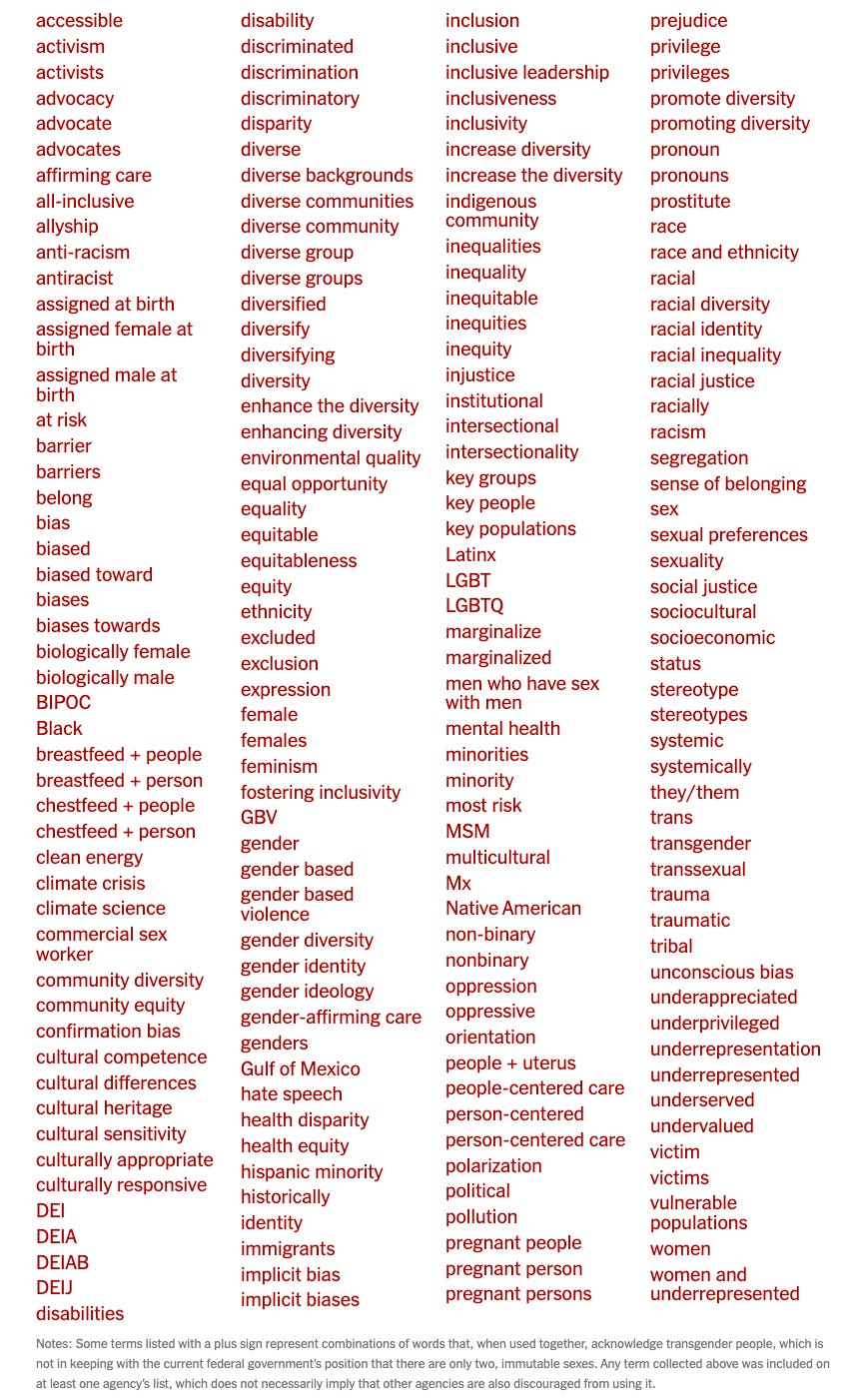

Only in dystopian fiction have I seen such brazen attacks on words themselves (1984 by George Orwell being a very pertinent example). Below is a list of words the Trump administration scoured funding databases for on the way to canceling federal grants that referenced them. Through one lens—the correct one, I would argue—these are excellent words that reflect a welcome breadth and depth of American history and efforts to make ourselves a stronger, more just democracy.

But the screeds coming out of Washington screed (new verb alert!) that these are “woke” ideas. Each gets a topsy-turvy twist. “Identity” is somehow racist even though people have always and forever “identified” in multiple ways (voluntarily or by force, hat-wearer or disco aficionado, tribal member or immigrant, etc.). When so many words associated with “identity” are also prohibited, it becomes impossible to argue for any word. The argument itself is dismissed as “woke.”

And that seems to be the point.

To silence. To shame. To shut down. And to exhaust.

As I was looking for a new kids’ book to write about, I wondered, “What addresses this moment for kids?” And then I felt awful for the young people becoming adults in this environment. Maybe the olds always feel this for the youngs. Yet I wonder if the challenges of now are especially acute.

This semester, I began Introduction to Human Rights by saying that I had never taught this subject in such a cataclysmic environment. Attacks on books and words, check. Efforts to dismantle universities (including the one where I work) and criminalize protests, check. Deporting legal immigrants and asylees to foreign prisons. What? The dismantling of the many post-World War II agreements meant to help preserve peace and foster prosperity? HUH?

And the lies. So many lies. Lies about budget cuts. Lies about health care. Lies about warrantless arrests and Qatari airplanes and habeas corpus. There is an entire book about Trump’s lies only in the first term. There are even lies about lies (like winning the 2020 election and the causes of January 6).

Why not search “lies,” I thought.

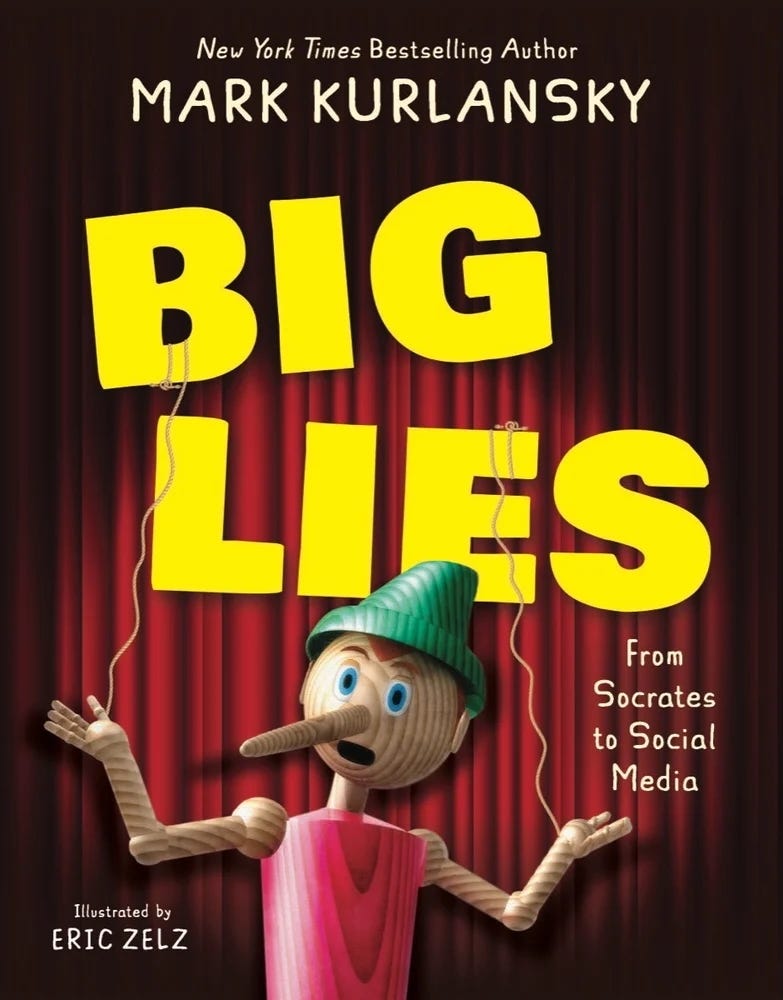

That’s about when I stumbled on Mark Kurlansky’s book, Big Lies: From Socrates to Social Media. Kurlansky is a wonderfully prolific writer who has tackled subjects as diverse as Cod (the fish), 1968: The Year that Rocked the World, and over thirty more (check out his website for a complete list).

As the title suggests, lies on a grand scale are nothing new. Kurlansky takes on this problem from the very first lines, inviting readers to see his book as a collection of his own “ideas, facts, and opinions…but I ask you consider as you read and to decide for yourself what to believe…That is how we struggle toward the truth, and it is a struggle that keeps the world from descending into chaos.”

That invitation is what makes this book so special and, I believe, effective for young readers. Kurlansky doesn’t bludgeon us with an “I’m right, they’re wrong” approach. Kurlansky firmly puts the power of critical thinking into our, the reader’s, hands.

By putting lies in a historical context, he also normalizes them in a way that drains some of the fear and bluster from the current moment. The urge to lie emerges early in humans and is evident even before the emergence of spoken language. Also, lying is not unique to humans. Some predators rely on deceit, a version of lying, to hunt. As Kurlansky notes, “The octopus, without shell or skeleton, relies on deceit to survive, adopting various shapes and colors to fool predators.”

Perhaps the fact that lying is everywhere is cold comfort to you (depending on my mood, it’s cold comfort to me as well). Kurlansky delivers example after example of how lies eventually wither in the face of truth. For the truth to prevail, however, there needs to be some system capable of contrasting the lie and the truth so that people can see the difference, ask more questions, and understand where the truth lies.

Defending our democracy is an important tool to counter lies.

In this age of social media and the sharply increasing use of artificial intelligence (which also lies, perhaps one of the most human of characteristics), telling the truth from lies will get even harder. And it’s not just the lies that are a problem. In my classroom, I see a real decline in the ability of students to apply the tools Kurlansky names to counter the effect of lies: read closely, evaluate, and ask lots of questions.

In important ways, Big Lies is exactly the kind of book we all need at this moment (I encourage adults to read it).

Take a breath, Kurlansky seems to be saying, we’ve been here before and this is what can be done to get to the truth.

And the design! It’s marvelous. Kurlansky worked with Eric Zelz, a wonderful illustrator of picture books, among other things. There are graphic novel sections, photographs, and great in-depth sidebars. The book, as well as being informative, often funny, and timely, is a joy to read.

Here’s my interview with Mark.

How did you come to embark on this project?

I saw kids bombarded with false and true information and not much skill at seeing the difference. I wanted to tell them that people have always lied and there are ways to tell the difference. Seeing people constantly googling for the answer to questions and paying no attention to what was the source of the answer they got disturbed me.

While your book is very timely, you also demonstrate that people have always told lies. Did that research surprise you? Was there one historical lie you were most shocked by?

I don't think anything shocks me anymore but there are some lies that infuriate me because they are repeated over and over again. One is that nuclear bombs were dropped on civilian cities to shorten the war and save lives. The Japanese wanted to surrender and the choice of targets was a horrendous war crime. And of course there are lies that I didn’t manage to squeeze into the book. That Texas was taken from the Mexicans for freedom from a dictatorship. Mexico didn't allow slavery and the Americans fought to preserve slavery in Texas.

Some consider lies necessary, for instance to make peace. Can you give an example of a good or permissible lie?

The Talmud allows that there are certain permissible lies. But I think that once you start lying there is no turning back. If you tell someone they look great and they are sick and really look terrible, I suppose that is a permissible lie. There is such a thing as pointlessly being truthful.

The current American president is an exceptional liar, as you note in the book. You put lies by politicians into a different and more dangerous category than the personal lies we might tell friends and family. Why is are these lies more dangerous? How can young readers best tell a politician’s lie from the truth? Why should a politician’s lies matter more?

Politicians tell lies to cover up the things they are doing. We need to know what they are doing and understand the consequences. Trump lies because he knows the truth would be unacceptable to most people.

How has writing this book shaped the way you look at America today? It seems that we are in a new and terrifying age of lies, with the power of social media distributing disinformation, misinformation, and propaganda with a click of a phone. How should young people think about social media in a time of lies?

People who grew up with the internet think of it as a great source of information. Those of us who didn't understand that all information is dubious. If information is more readily available, that does not make it true. It might mean the opposite. The sources of information need to be examined and the prejudices and goals of those giving information need to be considered. Sources need to be questioned much more.

What are your thoughts about the relationship between artificial intelligence and lies?

Artificial intelligence can be used for positive and negative goals, but it is certainly a dangerous tool in the wrong hands, a tool that is ideal for deception.

At a time when many books about controversial subjects are being banned, what has been the reaction to your book? What has been the best reaction you’ve had to the book?

This book received the most laudatory review I have ever received (interviewer note: maybe this one?). But the people who review books and the people who want to ban them are very different people.

The design of the book is fabulous. Some of the book is in the form of cartoons. Why was that important to you?

Book design is all in the hands of the publisher. If it works well, and I think it does, they are the ones who deserve the credit. It was my idea to use the graphic novel format. I have done this before. It is an effective tool for certain kinds of storytelling.

What’s next for you?

I have two books coming out in 2025. One is a novel called Cheesecake, which takes place entirely on one block of Manhattan. A diner tries to go upscale by offering an incomprehensible recipe for cheesecake from ancient Rome. It is historically the oldest known written recipe but no one understands it. It becomes popular and others copy. Everyone’s “authentic” version is completely different. It is a story about food and following recipes but also a story about how the gentrification of a neighborhood destroys people’s homes.

I also have a history book, The Boston Way, about a group of leading abolitionists in Boston who tried to end slavery without violence. They try to avert a Civil War because they believe that issues cannot be resolved through violence and if violence is used, it would take a hundred years for black people to get their rights, which turns out to be optimistic.

If you feel so moved, here are some things to do that might help make you feel less powerless against lies:

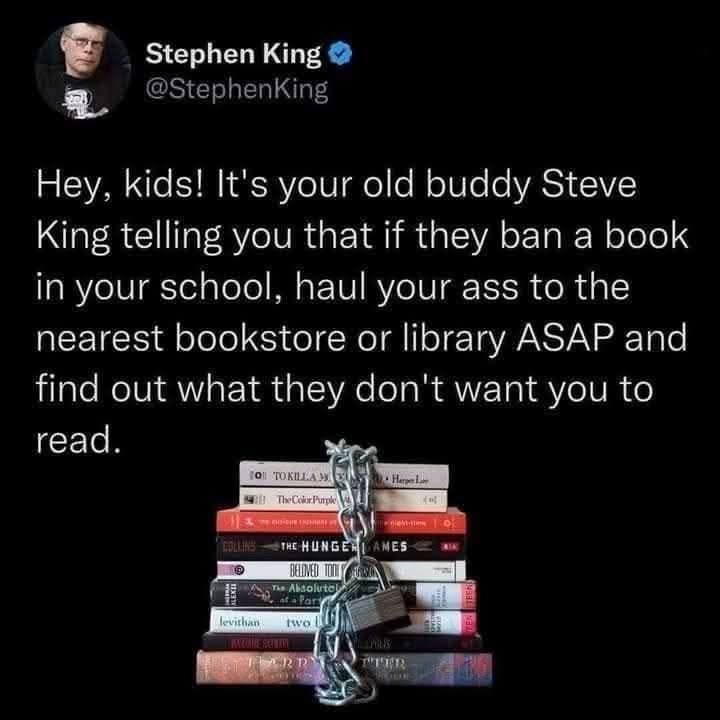

Read! There is power in reading—anything! Keep reading, sharing, discussing, and telling friends and family about the great stuff you are reading.

Send a Postcard to Your Local Library: Send a postcard to your library expressing your support.

Attend library events and help publicize them: Supporting your local library by showing up is crucial. Maybe it’s a read-a-story day or a talk (my library, the Durham County Library, has a fabulous series that has gone from local political events to hummingbirds, Afrofuturism, and the inauguration of a tool-lending library). If funding comes up at the town or country level, make sure the elected representatives know you support the library.

Call Congress to Save the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS): Urge your representatives to protect federal funding for libraries and museums and defeat the March 14th Executive Order set to decimate community access to information and privacy.

Thank you for reading!