Fred Korematsu Speaks Up

A lesson in activism for our times

Every American should know Fred Korematsu’s name.

Born in California in 1919, Korematsu had a typical American childhood. His parents, Japanese immigrants, ran a plant nursery in Oakland, California. He studied hard in school and fell in love.

Then World War II changed everything. Wanting to help, Korematsu tried to enlist in the U.S. National Guard and U.S. Coast Guard. However, recruiters turned him away because of his Japanese ancestry. Korematsu became a welder and worked on the Oakland docks. But he was soon fired, again due to his immigrant ancestry.

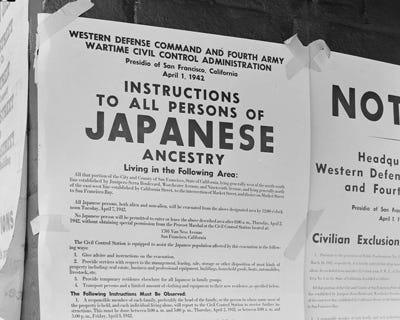

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the United States declared war on Japan and, a few days later, on Germany and its allies. For Korematsu, however, and so many immigrant families like his, a new and sinister campaign against them emerged within the United States. Deep prejudice and fear of Asians led to a presidential order compelling Japanese Americans living along the West Coast to submit to forced internment.

Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in February 1942, led to one of the darkest chapters in American history. Americans were detained not because of any crime they’d committed. Instead, the order was based solely on their ancestry. In the words of one US Supreme Court Justice in his objection to the program, “detention in Relocation Centers of persons of Japanese ancestry regardless of loyalty is not only unauthorized by Congress or the Executive but is another example of the unconstitutional resort to racism inherent in the entire evacuation program.”

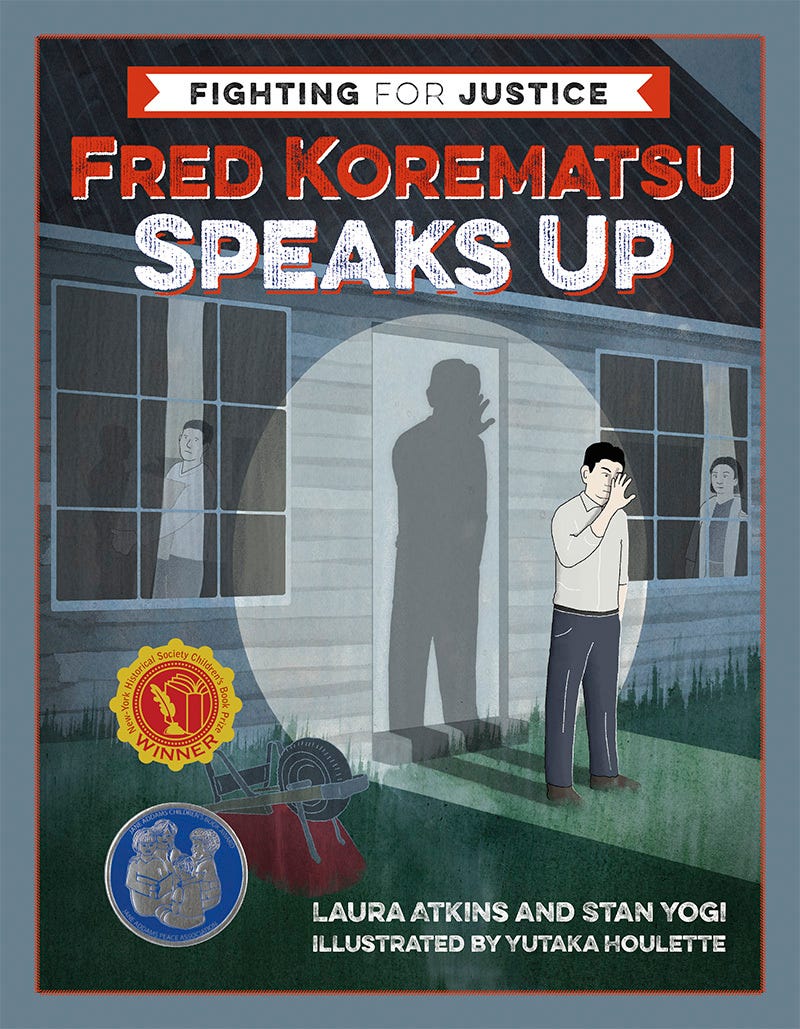

Laura Atkins and Stan Yogi’s book, Fred Korematsu Speaks Up, aims to introduce Korematsu to young readers and describes in vivid detail how he and others fought back against this injustice. The book is spectacular, aided by lively illustrations by Yutaka Houlette. When I say I was stunned and delighted by this book, I am not exaggerating. The writing, research, and visuals are among the best I’ve seen in a book for any audience.

As Atkins and Yogi describe, Korematsu refused to comply with the order. He was arrested and convicted of defying the government. Korematsu’s appeal reached the Supreme Court. But the majority ruled against him, arguing that military necessity justified forced incarceration.

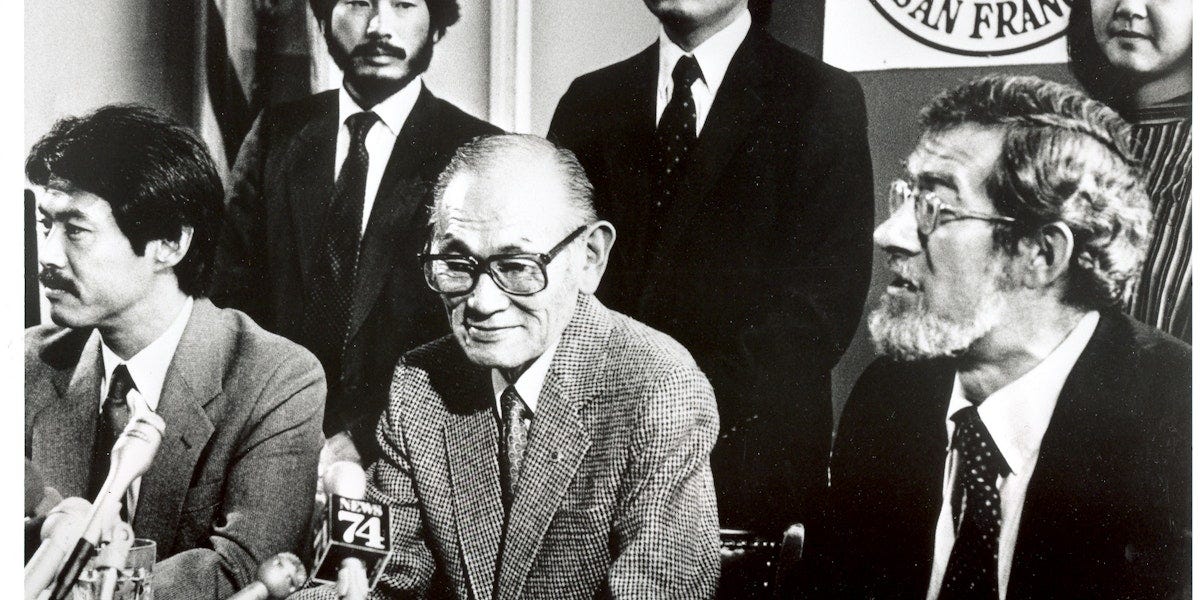

Later researchers were able to demonstrate that no such necessity had ever been documented. With Korematsu’s support, lawyers re-opened the case arguing official misconduct. On November 10, 1983, Korematsu’s conviction was overturned by a federal court, a pivotal moment in American civil rights history.

In 1998, President Bill Clinton awarded Korematsu the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

Korematsu didn’t just advocate on behalf of people like him. In the wake of anti-Muslim attacks after 9/11, Korematsu filed a “Friend of the Court” brief with the U.S. Supreme Court for cases involving discrimination against Muslim inmates at Guantánamo Bay. In those pages, he compared the government’s actions to what had been done against Japanese Americans.

I interviewed Atkins and Yogi about their excellent book.

How did you come to embark on this project?

Stan: I co-wrote, with my friend Elaine Elinson, Wherever There’s a Fight: How Runaway Slaves, Suffragists, Immigrants, Strikers and Poets Shaped Civil Liberties in California. After that book was released in 2009, our publisher, Malcolm Margolin of Heyday Books, wanted to create a children’s version. I thought that was a brilliant idea and raised my hand to work on the project. Over time, Malcolm’s idea morphed into a series of books, each one about a different person who spoke up for civil liberties and civil rights.

Laura: I came from a children’s book editing and writing background, with a focus on non-fiction. I was speaking on a panel on diverse publishing at the San Francisco Public Library, and editor Molly Woodward approached me afterwards. She asked if I could come on as a developmental editor, with the chance of co-writing. Stan and I worked together, including having Stan present Fred’s story to a group of 4th graders – our target audience. Eventually, I came on board as co-author, proposing the mixed format of the book, using poetic biographical narratives, and then more traditional non-fiction sections following. It looks kind of like a textbook, but a really engaging one!

This was such a painful part of American history yet it’s one we seem to keep veering toward. I’m thinking especially of Muslim Americans. What do you want your young readers to take away from the book?

Stan: Young people are attuned to justice. Think about how many times you’ve heard a child say, “That’s not fair.” I hope that Fred Korematsu Speaks Up helps young readers make the connection between injustices at a personal level and injustices in larger political contexts.

I also hope that the book educates them about how various groups of people have faced discrimination and hatred at different points in U.S. history, not because of anything they did but because of their race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, or other factors.

Finally, I hope that the book inspires young people to speak out against injustices in ways that are meaningful to them and that fit their passions.

Laura: I hope the book shows young readers that they don’t have to be “heroes” from the beginning. Fred Korematsu didn’t set out to change history. Originally, he refused to go to the prison camps because he wanted to be with his Italian-American girlfriend. And because he thought it was wrong for him and other Japanese Americans to be imprisoned when they had done nothing wrong. When the ACLU of Northern California asked if they could use his case to fight this imprisonment, he decided to say yes. It took one step, then another step, and after he lost that original U.S. Supreme Court case, he didn’t speak out again for a long time. When he did, it was with a team of pro bono lawyers who took his case. It took a village. All of us can participate, in whatever way we feel able, to speak up for justice.

One powerful theme is that one person building alliances can create a movement. Could you elaborate on how Fred Korematsu did that?

Stan: After Fred decided, in 1982, to challenge his criminal conviction of nearly 40 years earlier, he teamed up with two other men who had also been convicted for violating the government's World War II orders against Japanese Americans. They spoke around the country to educate people about the injustices they fought against decades earlier. At the same time, Fred was also involved with a grassroots group called the National Coalition for Redress and Reparations, which built political support for successful federal legislation to redress Japanese Americans who had been unjustly imprisoned during World War II.

Laura: Fred wasn’t just a lone hero who was born knowing he was going to change history. That’s such a common narrative in our books, including nonfiction for kids. The “hero’s journey” can focus on seemingly exceptional individuals.

But social change comes from movement – from mass action with ordinary people coming together to speak up for change.

Japanese Americans were a group that took action during the Muslim ban, and when immigrant children were being separated from their families. They felt solidarity with other groups facing discrimination. One of our goals in the book was not just to tell Fred’s story, but to include stories of people like Ralph Lazo, a young man from Los Angeles who went in solidarity to the prison camp with his Japanese American friends. There are so many stories to tell!

You and Laura Atkins did an immense amount of research for this book, which includes stunning visuals. What story or personality surprised you the most?

Stan: We ultimately didn’t include this in the book, but we learned that Theodore Geisel, otherwise known as Dr. Seuss, created propaganda cartoons during World War II that depicted Japanese Americans as racist caricatures and that promoted the false claim they were loyal to Japan.

Laura: I didn’t know that Japanese Americans in the Bay Area got sent to what was then a horse race track before going to prison camps in other parts of the country. And barracks were built, sometimes housing people in horse stalls. Fred Korematsu talked about his stall still smelled like horse manure. I was ashamed to read about this, and the broader treatment of Japanese Americans during this part of our history.

How has writing this book shaped the way you think about how young people are brought to action in favor of making the world a better place?

Stan: Laura coached me about how to inspire younger readers to act for justice. She taught me about helping young people to identify with a character (in this case Fred) through experiences with which they’re familiar, like getting a haircut, and, in Fred’s case, a barber refusing to cut his hair. (That scene opens our book.) The process of co-writing the book also helped me to share the message that we don’t need loud, big personalities to make a difference in the world. We just have to understand the issues we’re passionate about and discover the ways we can channel our unique abilities and skills to help address those issues – the stone soup method of community building and activism.

Laura: I think the collaborative process taught me a lot, and kind of mimicked or walked the talk of the message of the book. We had our amazing editor, Molly Woodward. We got feedback from lots of other people on the book, from different points of view. We read other books, including an advance copy of a biography for adults written by Lorraine Bannai, one of Fred Korematsu’s original pro-bono attorneys. I feel like our community process helped to create a book that embodies the value of people using creativity to teach and learn about history and engage with our stories.

At a time when political books for young people are being banned, what has been the reaction to your book? What has been the best reaction you’ve had to the book?

Stan: Heyday Books released Fred Korematsu Speaks Up in January 2017, right after Donald Trump entered the White House and there was widespread concern that his administration would roll back civil rights and erode democratic norms. Consequently, there was immediate interest in our book, especially from educators and parents. Laura and I have given presentations across the country about Fred’s story and the incarceration of Japanese Americans. We’ve spoken to about 8,000 students.

One of our most memorable interactions took place at the Fred Korematsu Elementary School in Davis, California. At the end of our presentation, we asked the students how they can be like Fred and speak up for what they think is right. Three girls raised their hands in excitement. They told us that vandals had recently defaced their mosque. Rather than saying they were fearful or angry about the attack, they explained how they had organized a fundraiser to help raise money to repair the damage. Stories like that inspire me.

Laura: As far as I know, our book hasn’t been banned. Yet. We’ve had so much love for the book. One of the most moving experiences was speaking over two days to a community college in southern California. We spoke to ESL students, including two who came and told me and Stan this was the first book they’d ever owned (the school donated copies to everyone). And that it was the first book they’d read in full. These were Latinx immigrants, and they strongly related to Fred Korematsu’s story.

I was stunned by how lively the book is visually. The pages really draw the reader in and are so rich. How was that process for you?

Stand: Laura and I were extremely fortunate to work with Yutaka Houlette, who crafted the evocative illustrations that bring Fred’s story alive. Yutaka read a draft of our book and created images that capture the emotional resonance of key moments in Fred’s life. It was very easy working with Yutaka. Laura and I had very little substantive feedback about how he could revise his illustrations.

Selecting the other visual elements of the book was fun. Because I co-wrote Wherever There’s a Fight, and because I’ve been involved with civil rights activism, especially for Asian American communities, I knew of many of the visual resources that we included in the book, but I also did online research to identify additional images. Our wonderful editor, Molly Woodward, also uncovered some incredible images.

Laura: A lot of credit also goes to the art director at Heyday, Diane Lee, and the freelance designer who worked on the book, Nancy Austin. We pulled together so many different visual elements, first using a big messy Google doc. Stan and Molly worked on getting permissions for the images. Phew! And the team pulled it all together.

What’s next for you?

Stan: I’m researching and writing a history (for adult readers, not kids) about U.S. Christians’ support for reproductive justice and LGBTQ+ equality.

Laura: I have a picture book I co-authored with veteran voting rights activists Edward Hailes and Jennifer Lai-Peterson coming out. It’s called Calling All Future Voters! and releases in September. We are holding an event for educators and anyone who wants to come on September 5th. People can find out more here.

Thanks for reading!

Excellent interview!

Thanks so much for interviewing us! And for sharing Fred Korematsu’s story and the story of our book.