The Burning

TL;DR: Writing about atrocity for young adults

In 1921, Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood was thriving.

Only fifteen years since its founding, Greenwood was a magnet for Black families eager to prosper. Greenwood had Black-owned shops and theaters, Black-owned banks and insurance agencies, Black-owned restaurants, and Black-owned and written newspapers.

Churches thrived as did Black-run associations of merchants and teachers. Fighting both racism and sexism, Black women were successful entrepreneurs, among them Mary E. Jones Parrish, who ran a typing school. Nearby, Mabel B. Little cut hair at her own beauty salon.

With roughly 10,000 residents, Greenwood was a model of what intellectual and rights activist W. E. B. DuBois called (using the vernacular of the time), “the new hope and power of the colored folk.”

One way Black people built power was by supporting each other. Despite ferocious and rising white supremacist violence, the over 10,000 Greenwood residents bought from each other, hired each other, and paid each other, detouring around the Jim Crow laws that enforced segregation and relegated them to second-class and often excluded status.

Greenwood’s success stoked resentment by whites furious that Black Americans were jumping ahead of them in prosperity.

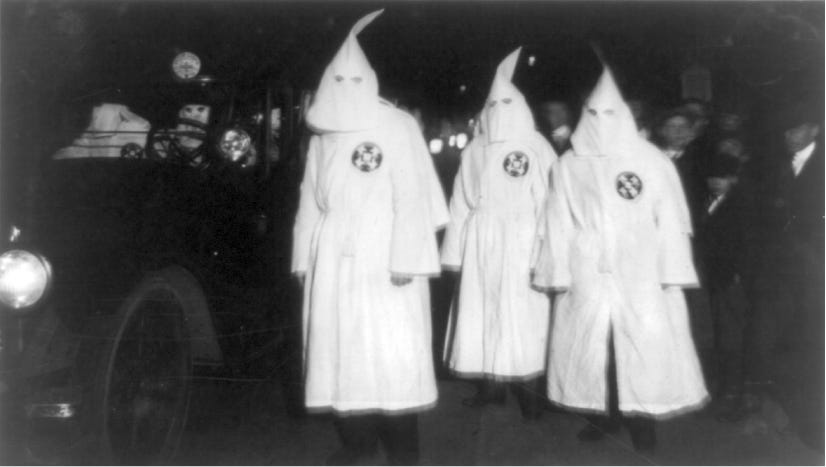

That prosperity was quashed dramatically on May 31 and June 1, 1921—103 years ago this week. In the 1920s, White supremacy was dramatically rising. Millions of white Americans belonged to violent groups like the Ku Klux Klan. For them, neighborhoods like Greenwood were a glaring refutation of their deeply racist views.

On May 31, Tulsa police arrested Dick Rowland, a young Black man, and falsely accused him of attempted rape (National Geographic did an excellent moment-by-moment reconstruction of the events). This was a dangerously common pretext for lynching: torturing and hanging the innocent. That night, armed Blacks and whites faced off at gunpoint. Tensions calmed but in the morning, a well-organized mob of thousands of white people surged into Greenwood and set it on fire. Attackers even used airplanes to drop sticks of dynamite on the neighborhood, making Tulsa the first American city to ever be assaulted by air.

By the time the ashes cooled, as many as 300 people were dead. Thousands were homeless, a lifetime’s worth of work and investment in ruins. More than 1,400 homes and businesses were burned or looted. The famed Negro Wall Street of America was no more.

For the centennial of the Tulsa Massacre, the New York Times did an excellent before and after visual report.

As a boy, Tim Madigan knew nothing about these events. In that, he was like most white Americans, unaware of frequent and brutal acts of racial violence. I understand that reality. Although I grew up in Chicago and my mother’s family is deeply rooted in the city, I was in my 50s when I first read about the so-called “Red Summer” of 1919 (check out Martin Sandler’s excellent 1919: the year that changed America).

That year, Eugene Williams, a Black seventeen-year-old, inadvertently drifted across the invisible line that segregated a Lake Michigan beach. Whites began throwing stones. Tragically, Williams drowned. Police refused to arrest the alleged murderers. Unrest exploded and white mobs attached Black people throughout the city. Seven days later, 23 Black people and 15 white people were dead.

As Madigan describes in his interview with me about his book about the Tulsa Massacre, The Burning, he came to the story “Wholly by accident…or fate.” Even as an adult, he didn’t know much about what had happened in Tulsa. It was only when his editor at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram gave him a wire story to follow up on that he began digging.

I wanted to interview Tim about his excellent book not only because of its riveting and timely exploration of why Tulsa matters today. The book has also been adapted into a young adult version (with the same title) by acclaimed author Hilary Beard.

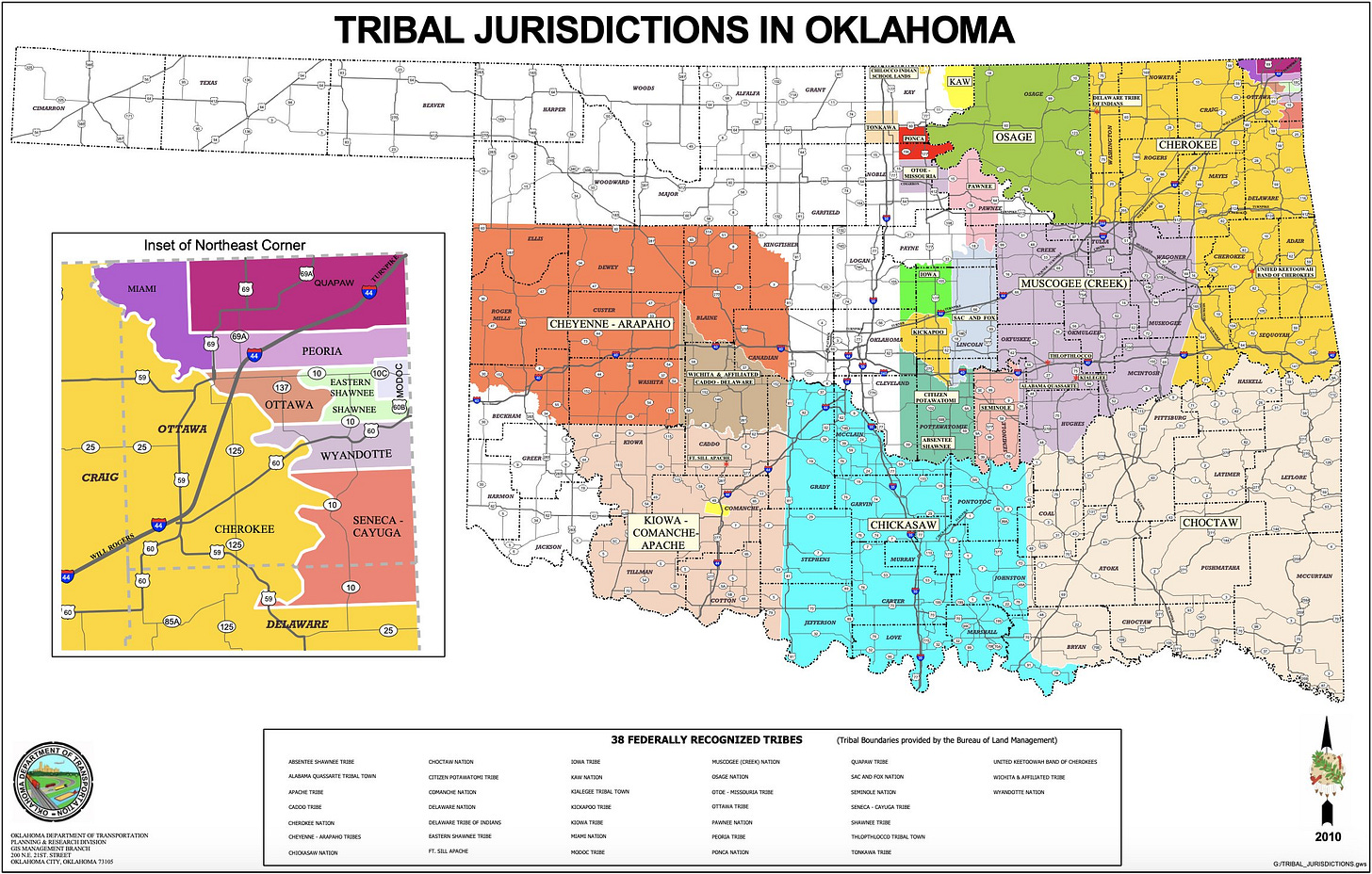

Beard started the adaptation knowing more about Tulsa than Madigan had as he started his book. Beard told me in an interview that she believed she could contribute insights to the story rooted in her experience as a Black woman. For her, the fact that the massacre took place on Native American land and that Native Americans were subjected to genocide were crucial to the story.

As a writer and human rights advocate, I think a lot about how we present these important stories to young people. We must make sure future generations aren’t like Tim’s and mine, unaware of the violent and difficult parts of our past. At the same time, these stories also show younger readers the astonishing vitality, persistence, and ingenuity of Black communities even in the face of extreme violence (and it’s exciting that basketball superstar LeBron James’s production company is at work on a documentary about the Tulsa Massacre).

Book banners hate these kinds of books since they tell hard histories that many want to continue to suppress. But I want to lift these stories up so that everyone can learn from what rights champion Pauli Murray called “both the degradation and the dignity of all of our ancestors.”

INTERVIEW WITH TIM MADIGAN

Tim, how did you come to write The Burning?

Wholly by accident…or fate. I was born and raised in northern Minnesota where there are virtually no black people. Even after I moved to Texas in the early 1980s, the experience of African Americans in the United States and the struggles they continued to endure just wasn’t on my personal radar screen. Then, in January 2000, my editor at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram handed me a wire service story about what was then called the Tulsa Race Riot. (In recent years it has become more accurately described as a massacre.) That day, I read for the first time about this atrocity—a mob of up to 10,000 whites surrounding the prosperous Black community in Tulsa that was called Greenwood.

After a preordained signal in the early morning of June 1, 1921, the mob attacked and completely destroyed the community—killing up to 300 people.

I looked at my editor that day and said, “This can’t be true. Anything this terrible we would have known about.” That was her reaction, too.

She sent me to Tulsa to write a piece about the massacre that eventually ran under the headline, “Tulsa’s Terrible Secret.” A short time later, a literary agent called to ask if I would be interested in developing the piece into a book. It went on from there.

How has writing this book shaped the way you think about American history?

It utterly transformed it. Until then, I’m not proud to admit, I knew practically nothing about African American history, especially the horrible times after the Civil War. For my book research I learned that history, really for the first time, because I knew I needed to put Tulsa into the proper historical context. I was stunned and horrified by what I learned. What happened to the Greenwood community was not some historical anomaly, but completely consistent with what was happening at that moment in the U.S. Jim Crow. Racial violence and racial terror lynching. So-called “race riots” that occurred in towns and cities across the nation, (really just excuses for enraged white mobs to attack blacks). Virulent racism is deeply baked into our society and culture at the highest levels, both North and South. On and on. It really changed me as a person.

Early in your research, you approached Don Ross, an Oklahoma state representative who devoted himself to recovering the Tulsa story. He challenged you for not already knowing about Tulsa. How do you convince White people to read books like The Burning?

In 1995, through my newspaper work, I met Fred Rogers, the icon of children’s television. From then until his death eight years later, he and I were very close friends. He truly was one of civilization’s greatest human beings.

One of my favorite quotes from Fred was this one, “It’s much easier to love someone when you know their story.”

Rogers used that principle to mentor me through a complicated relationship with my father, coaxing me to learn my dad’s story. Once I did, it completely changed the way I looked at him and it healed much of my pain. The same was true for me once I learned our race history. It changed the way I looked at people different than myself and hopefully made me more compassionate and curious.

As hard as this history is, we shouldn’t learn it just as a favor or an obligation to African Americans. We should learn it as a favor to ourselves.

Learning makes us better people. That is what is so sad about the recent pushback against teaching this material in our schools.

Were there things you read as you researched this material that particularly moved, shocked, or inspired you?

As I’ve said, because of my near-total ignorance, nearly everything I learned shocked me. I’m inspired by the resilience of Black people, who rebuilt Greenwood despite significant efforts by white Tulsa leaders to keep them from doing so. The African American story is about so much more than victimization. I’ve come across this phrase, “in spite of,” what Blacks have achieved in the nation in spite of the obstacles and horrors arrayed against them.

At a time when books about Black history are being banned, what has been the reaction to your book? What has been the best reaction you’ve had to the book?

The Burning got great reviews in all the right places at the time it was published in 2001, but sold very modestly until 2019, when it was cited as important source material for the opening scenes of HBO’s Emmy-winning series, Watchmen, graphic depictions of the Tulsa Massacre. The Burning became a New York Times bestseller in 2021. And over and over again, I have heard about readers who responded to the material the same way I did. First, they say, “I never knew.” Then they say, “I feel like a different person for knowing this.”

When you were a kid, what were some of your favorite books?

I was a huge reader when I was a kid, and have wanted to be a writer nearly all my life. I remember I really loved Sherlock Holmes mysteries from a young age.

It’s often said that the primary difference between books for adults and books for younger readers is hope. Children need to see hope in what they read. Is there a hopeful message in The Burning?

I think the truth, even if it’s difficult, brings hope. There is something terribly corrosive for all people, young and old, when the truth is buried or whitewashed. We know something is wrong, but without the truth, it feels as if we are swinging at ghosts. And then there is what I said before, about learning the truth making us better people. I have this vision of a classroom somewhere, where this material (hopefully my book) is being taught. At the end of the lesson, a young white student looks over at a young Black classmate, and sees that classmate differently, with greater humanity and curiosity. That’s what happened to me.

What’s next for you?

We’ve adapted my Mister Rogers book into a play, “I’m Proud of You,” that I think will be very successful. And I’m currently in the middle of a deep dive into Native American history, more specifically the history of the Lakota Sioux. Again, until recently I knew so little about this, and the parallels between that history and African American history are striking. So there is more truth to be told.

INTERVIEW WITH HILARY BEARD

What did you think when you were first approached to adapt The Burning for young readers?

I was excited to be invited to adapt The Burning and was interested in learning more about the Tulsa Massacre and this part of American history. It’s hard history and I already knew a good bit about it. But adapting Tim’s book gave me the opportunity to use my gifts as a researcher and writer to bring the story to young adults.

I had a tremendous amount of respect for Tim’s research and craftsmanship as well as the tremendous care he, a White man, took telling Black people’s stories. I wanted to contextualize the Massacre by framing it both within American history and within African Americans’ struggle for freedom and justice and to be seen as fully human.

I also aspired to layer in insights about Black history and life that I have as a Black woman that Tim did not. The Tulsa massacre took place on Native American soil, and Native Americans were experiencing genocide, which is ongoing. African Americans and Native Americans had important relationships on this land. I wanted to include that history as well.

I also wanted to elevate stories of heroism, ingenuity, and brilliance as African Americans emerged from enslavement and Reconstruction and attempted to navigate Jim Crow segregation.

Narratives of White-on-Black violence in this country continue to be suppressed, though to a great degree White supremacist violence has been a norm. For example, in my own family, the first 10 years of the lives of both of my maternal grandparents were bookended by lynchings of Black men, where thousands of people came for miles to watch—and this was in the North.

On my father’s side, my paternal grandparents experienced at least three race massacres and several lynchings during the first 25 years of their lives. My parents participated in the Civil Rights Movement, but I have experienced racial violence in my lifetime as well. So to me, these narratives are a continuum having to do with the American story, which includes Black heroism.

The fact that we don’t acknowledge and confront hard history like this is part of the reason White supremacy and White nationalism threaten our nation and democracy today. I saw adapting Tim’s book as an opportunity to bring suppressed history to light so we have the chance to heal, individually and collectively.

So much of this story is brutal and shocking. How did you approach adapting the story for younger readers?

First, this is a young adult book that skews to the older teenager and quite honestly would challenge any adult. Violence isn’t developmentally appropriate for any human being of any age. I wanted to find a balance, where I told the story accurately and comprehensively but left out most of the blood and guts and horror, so young readers wouldn’t be traumatized.

That said, in school, students learn lots of hard history, from countless battles and wars—the American Revolution, the War of 1812, the Civil War, all the way to the present—to the Trail of Tears and Native American genocide, the Abolitionist Movement, the Holocaust, Japanese Internment, the Civil Rights Movement, 9/11.

The Tulsa Massacre and the countless other race massacres have been intentionally omitted from the narrative but are a part of American history and are as important as other difficult and even horrific events.

I don't underestimate young adults’ ability to find meaning or inspiration within stories about how people dealt with the difficulties they faced and the resilience they demonstrated facing down the challenges of their era. Many young readers also deal with the structural violence of poverty, underfunded schools, lack of broadband access, and so on. We're having difficult conversations right now about protests on college campuses and anti-Semitism and Islamophobia. We’re talking about mental health and addiction. Young people have the capacity and desire to think about and to discuss difficult topics. Many demonstrate tremendous empathy toward each other, which creates the possibility of a more human society and world.

Were there things you read as you worked on this manuscript that particularly moved, shocked, or inspired you?

I’m inspired by the resilience of Black people coming out of enslavement. Without resources, they envisioned and had the courage to create a place they thought of as a promised land, where they could be safe, start farms and businesses, and raise their families.

The collective work and cooperation that caused the Greenwood community of Tulsa to be called Black Wall Street was very compelling. One dollar circulated through that community somewhere between 19 and 31 times as Black people supported each other in the face of Jim Crow segregation, oppression, and violence. I think it’s fabulous that Loula T. Williams, who opened the Dreamland Theatre in 1914, was banking the equivalent of $800,000 a year through hard work and ingenuity. Centenarians who survived the massacre are still demanding justice. The Tulsans who fought for decades to bring this story to light – all of these inspire me.

On the flipside, the brutality of the thousands of White Tulsans who took part in the Massacre took my breath away. So did the conspiracy between so many of the city’s institutions and so-called upstanding citizens—politicians, law enforcement, bankers, insurance companies, realtors, and so on—to further disempower Black Tulsans, even after these same leaders terrorized them and burned their homes and businesses down.

What is your recommendation to educators who want to use this book in their classroom? I know there is a teacher’s guide but my question goes a little deeper. How do you think teachers should deal with the emotional side of this for young people?

I think teachers should be as thoughtful with this book as they are with, say, teaching the Holocaust. The Massacre was horrific. Teachers should first explore and navigate their own racial stress. They have to manage and reflect on their own emotions to help young people process their emotions and create space to talk about the issues and how many are still operative today.

Students may not want to sit still. They may want to express themselves through art. Or they may want to sit quietly. Allowing people to stretch or express emotion, do their own writing and journalism or paint and color would be my suggestions. Teachers should create room for people to navigate their emotions and tell their own stories.

How have your presentations with this book gone?

People are very surprised even shocked to learn this history and about the prevalence of White-on-Black violence. In all, they have been very interested in the story. I present the Tulsa Massacre within the continuum of Black people’s many heroic efforts to create a place for themselves in our society and to the struggle to create a multiracial democracy. The feedback has been extremely positive. Many people are hungry for truth and a more complex American story.

It’s often said that the primary difference between books for adults and books for younger readers is hope. Children need to see hope in what they read. Is there a hopeful message in The Burning?

Hope is really important. Black people left enslavement oftentimes barefoot and with just the clothes on their backs and walked for weeks with the hope of creating a Promised Land where they could be safe, free, and have farms and businesses to provide for themselves. They were so successful that some White people became jealous of their success in various locations around the country. Black Tulsans rebuilt Black Wall Street even as the city tried to sabotage their efforts.

Once people know the truth, they can address the world as it is rather than the fairytale American story we so often like to tell. Knowing the truth helps also people have empathy with each other and understand each other’s stories. There is hope in that. I think it’s also hopeful and positive that we are learning more of these positive stories about Black and Brown people. All of us need to see ourselves and each other in stories. And in seeing our brilliance and resilience we find hope.

When you were a kid, what were some of your favorite books?

When I was a teenager I loved The Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison. I read The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities and Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. Nancy Drew and The Hardy Boys mysteries. I read The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien for the first time as a teenager. My father had on his shelf books by Edgar Allen Poe and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. I think I read Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery as a teenager. A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith. But there really weren’t many books about people like me.

I was born a writer. In my baby book, my mother wrote that I was always trying to write something.

Thank you for reading!