When I teach my Introduction to Human Rights course, I always begin with two tried and true approaches.

One is a simple thought exercise that asks students to consider behavior that’s unacceptable in the classroom. Barring an act of violence, I ask, what is the worst thing a student can do while in class?

When I’d ask this question 10 years ago, I received a very specific answer [wait for it]. The answers I receive now are different and very much reflect the dramatic changes that have taken place in the world, the country, and at my university.

Ten years ago, the answer was to wear to class a certain powder blue t-shirt celebrating a certain state university that is also a basketball powerhouse and is located a couple of miles to the southwest. I suspect students still think this but other behaviors are either more top-of-mind or more socially acceptable to say out loud, with your peers listening.

I attribute this shift in part to how the university has changed its admissions strategy. Students today are equally accomplished, driven, and bright. But there is a much lower percentage of students who self-identify as White: from 71.9 percent in 2000 to 43.7 in 2021. The increase in Asian-identifying students is especially notable, from 11.7 percent in 2000 to 27.5 in 2021. The university has also increasingly recruited first-generation, low-income, and international students.

Today, students say that saying racist things wouldn’t be tolerated. Failing to use the proper pronouns is a no-no as is making fun of someone because of their identity or a disability. A lot of what is right and wrong—and the roots of how we think about human rights—are dependent on our community and expanding ideas of who is considered human and deserving of rights.

Ideas about right and wrong can change dramatically over time even in the same location. For me, this is crucial to understanding human rights as not some immutable set of norms but a changing reflection of human beings adjusting to new understandings of what it means to be human.

The second approach I use to teach human rights has to do with a lost letter.

Even as the Enlightenment was churning out ideas about rights (the English Bill of Rights, the US Constitution, the French Declaration on the Rights of Man), Europe benefitted from two enormous and lucrative atrocities: the transatlantic slave trade and colonialism/imperialism, including the Conquest of the Americas. I tell the amazing story about how a ragged group of Spanish adventurers, after multiple failed attempts, finally stepped ashore near the modern town of Tumbes, in contemporary Peru, then conquered an empire.

It’s a fascinating story, memorably told in one of my favorite books, John Hemming’s The Conquest of the Incas.

The conquest was brutal, as Francisco Pizarro ambushed, ransomed, then killed the ruling Inca, Atahualpa. As they had in the Caribbean, Central America, and Mexico, the Spanish moved quickly and violently to eradicate resistance, compel Catholicism at swordpoint, seize natural resources, including precious metals like gold, and impose the plantation (encomienda) system, which robbed indigenous communities of commonly-held land and resources.

One Spanish priest, Bartolomé de las Casas, writing from his base in what is now the Dominican Republic, eventually became horrified with how the conquerors treated Indigenous populations. Las Casas advocated for—and won—reforms, some of which helped and some of which were never adopted. Yet his arguments and example resonated through the centuries and lie at the root of new understandings and protections of of Indigenous rights

I use the example of Las Casas to show that support for the Conquest was by no means unanimous. Las Casas and his allies were a clear minority. Yet he and others saw indigenous people as human and as rights-holders in ways that, while not decisive, remained meaningful. Due to his influence, some rights were returned to Indigenous communities, who were eventually allowed some control over their internal affairs.

It’s important to recognize that De Las Casas continued to embrace European superiority and believed that Christians should convert so-called “heathens” to save their souls. For a time, he supported importing enslaved people from Africa to the Americas, an opinion he came to regret.

This was both a deeply personal realization and the beginning of a profound change in how Las Casas lived. At age thirty, he gave up his encomienda and the Indigenous workers there and later refused to grant forgiveness to any Christian who did not do the same.

Las Casas was willing to be controversial—and unpopular. As I wrote in the introduction to Righting Wrongs: 20 human rights heroes around the world, his convictions needled his colleagues. Once, a bishop grew tired of Las Casas constantly talking about the deaths of thousands of Indigenous children. “What is that to me and to the king?” the bishop complained.

“What is it to your lordship and to the king that those souls die?” Las Casas reportedly responded. “Oh, great and eternal God! Who is there to whom that is something?”1

Las Casas spent the rest of his life writing dozens of books and letters exposing the atrocities of the conquest and attempting to convince the king and his advisers to curb abuses against Indigenous people. His most famous book is In Defense of the Indians, which remains widely studied today.

But there was another and even more dramatic example of how principled opposition can emerge and resonate. Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala, or Falcon Cougar in Quechua, the ancient Inca language, was an Indigenous man born in about 1535, when Las Casas would have been 51 (the priest died in 1566). Falcon Cougar likely learned to read and write from Spanish priests (the Inca had no written language).

Starting in about 1600, Falcon Cougar started El primer nueva corónica [sic] y buen gobierno (The First New Chronicle and Good Government), a 1,189-page letter, later recognized as the longest critique of the Conquest and Spanish rule produced by an Indigenous person. Falcon Cougar not only called out abuses of the Spanish conquerors. He opposed the Conquest itself as illegal and immoral, something Las Casas never did.

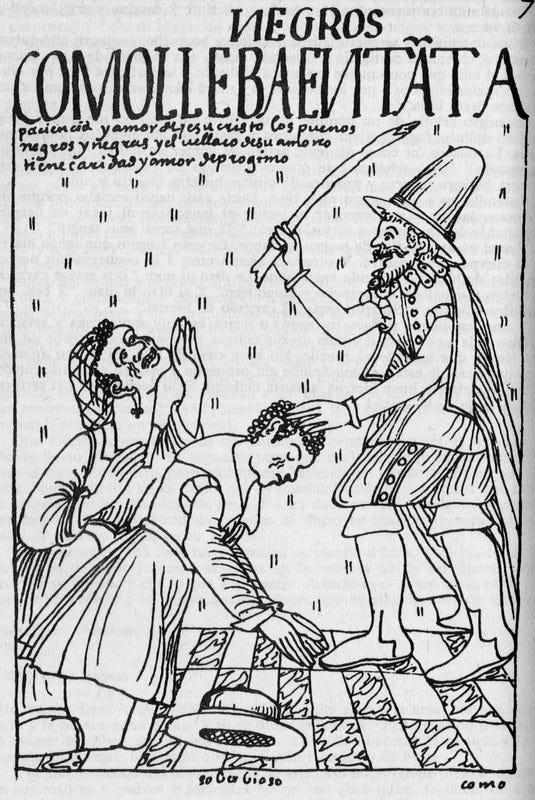

In addition to the text, Falcon Cougar included 398 of his own line drawings (as I tell students, the IMAX or Tiktok of the day) as well as a detailed map of the former Inca Empire.

Other drawings relate to Inca history or customs. But Falcon Cougar also included many drawings representing atrocities committed by the Spanish and meant to moves the king’s heart. One of the most fascinating depicts Africans forcibly transported to the New World in chains.

While Las Casas’ work was (and is) widely circulated, Falcon Cougar’s letter never made it to the King. Not long after its completion, the letter traveled to Europe and was placed in the Danish Royal Library, where a researcher stumbled across it in 1908. Heavily damaged, the pages reproduced here have been heavily retouched. The complete manuscript is available online here.

My message to students who engage with this material is this: there are always abuses or atrocities that most people think of as normal or “just the way things are.” But there is also always a minority that can be grown into a majority to denounce these violations and make the change necessary to prevent or criminalize them.

Ideas of human rights change. It’s up to new generations to expand and defend more expansive understandings of what it means to be human and have rights.

Book News

2022 has turned into quite a year for new publishing ventures from me.

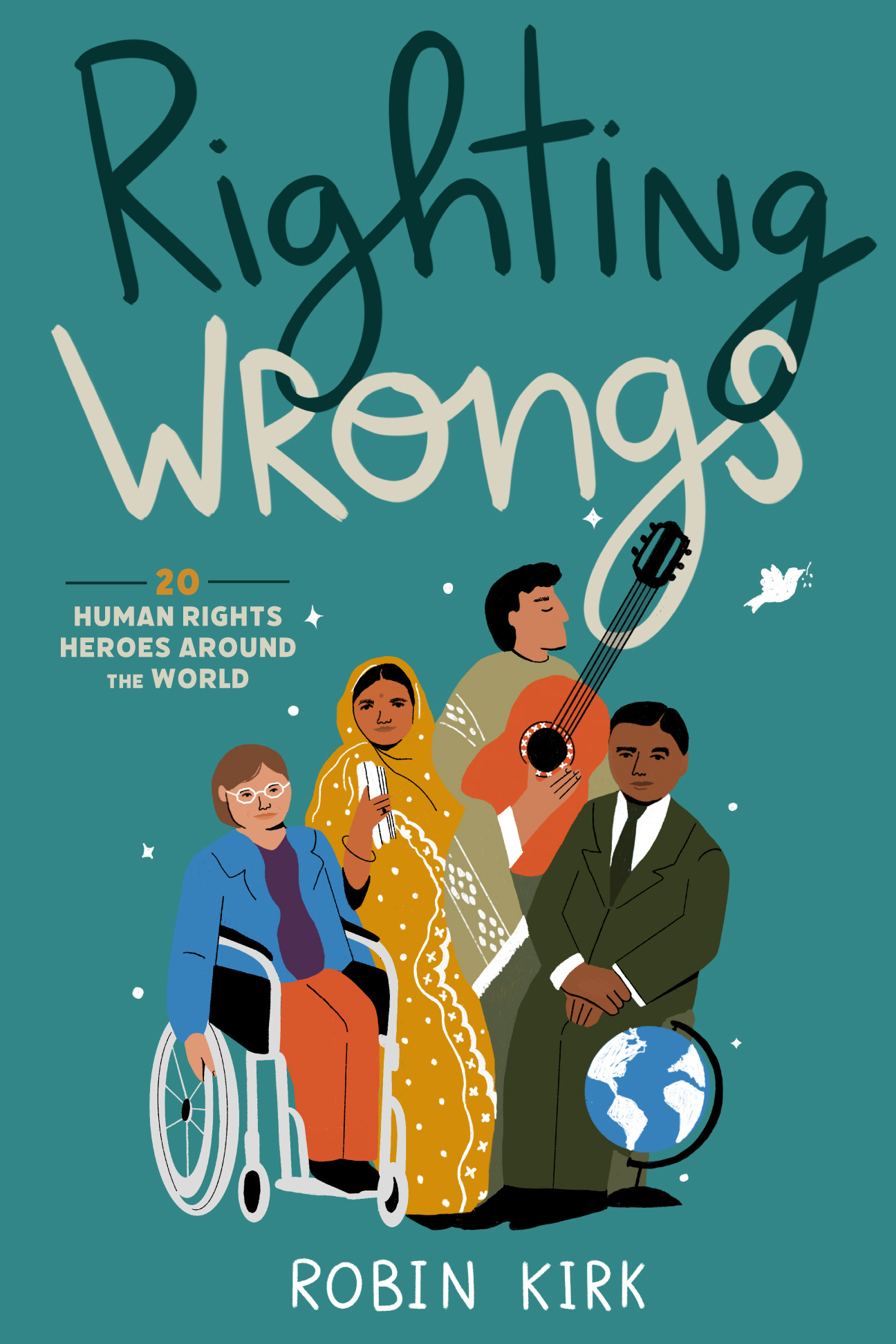

The book I refer to here (and whose Introduction goes into more detail about Las Casas and Falcom Cougar) isRighting Wrongs: 20 human rights heroes around the world. Righting Wrongs releases on June 6 from Chicago Review Press. Already, my book is available for preorder via the publisher’s website.

As always, preorders help authors tremendously.

The book melds my experiences as a human rights advocate with my years teaching human rights at Duke University (and helping to found and currently co-direct the Duke Human Rights Center@the Franklin Humanities Institute).

I couldn’t be more thrilled with how the book turned out. The cover and interior art, by Ana Paiva, makes me happy every time I see it.

Can you identify the four heroes on the cover? HINT: I chose each of these 20 heroes for two reasons: they’d made significant contributions to human rights and were relatively unknown. SECOND HINT: US-INDIA-CHILE-US (thanks Guardian Saturday quiz!)

Also, stay tuned for news about the September re-release of The Bond Trilogy: The Bond, The Hive Queen, and (for the first time!) The Mother’s Wheel. The books will have new covers, a new interior design, and (drum roll) new content. If you are interested in receiving an eARC of any of the books in exchange for an early review, please contact me!

#SundaySentence

I’m a huge Margaret Atwood fan so ate up this recent Guardian interview with her by Hadley Freeman. Also, #SundaySentence is a great follow, with the best lines people have come across in their readings that week.

Thanks for reading! Without the support of readers like you, I wouldn't enjoy doing what I do nearly as much.

Website * Instagram * Twitter * Facebook * LinkedIn

Ellsberg, Robert. “Las Casas’ Discovery: What the ‘Protector of the Indians’ Found in America.” America Magazine, November 5, 2012.